Unleashing the Power of Shimcache with Chainsaw

Novel Analysis Methods for Shimcache

Introduction

WithSecure™ Incident Response team has released a new subcommand for the Chainsaw forensic tool named “analyse”. This new subcommand incorporates three innovative and novel techniques to aid the analysis and timestamp enrichment of Shimcache entries. This plug-in has been included with Chainsaw v2.6 and is available from the WithSecureLabs GitHub.

This subcommand enables incident responders to attribute specific timeframes to the entries within Shimcache data. This new capability represents a significant advancement in analysis and offers a powerful tool to enrich Shimcache data in a way not available previously.

In this blog post, we will delve into the details of the analysis techniques used by the WithSecure™ Incident Response team and explore how they enable us to derive timestamps for Shimcache entries.

Background

WithSecure™ Incident Response team was engaged in responding to a significant security breach linked to the notorious CozyBear/APT29 threat group. Utilizing the advanced capabilities of the WithSecure™ Under Attack service, which includes the deployment of the WithSecure™ EDR agent, our team swiftly obtained a comprehensive understanding of the compromise. Within the 72-hour triage period, we discovered that the threat actor had infiltrated the network several months prior, effectively spying on the key personnel by using the M365 legacy authentication methods and Cobalt Strike beacons on compromised devices. While we were able to confidently contain the incident, a crucial question remained unresolved: how long had APT29 been monitoring the critical personnel within the organization?

Unfortunately, security monitoring was not in place, and the default log retention failed to encompass the entire duration of the compromise. However, we had a breakthrough when we discovered that the threat actor's TTPs (tactics, techniques, and procedures) could be consistently observed within the Shimcache. However, despite its usefulness, the Shimcache does not provide timestamps of activity, presenting a unique hurdle for our investigation. While we knew that we could not obtain exact timestamps, our team sought to determine if it was possible to derive timeframes indicating when the threat actor's activities took place.

Looking at the Shimcache from this perspective led us to novel analysis techniques (Technique 1 and 3) of the Shimcache that enabled us to pinpoint the initial threat actor activity, with a granularity of one minute. This information subsequently allowed our team to determine the initial date of compromise and, crucially, identify patient zero. Thus, answering the critical question of how long the threat actor had been spying on key personnel.

Following the identification of the techniques, the main challenge with deriving timestamp information from Shimcache data was that those existing techniques required the use of multiple open-source tools which could not be streamlined. Thanks to the funding secured from the EU-funded CC-Driver project, Markus Tuominen was able to complete the research and successfully incorporate this analysis method into Chainsaw. This research not only built upon our initial knowledge/techniques but also added new techniques and identified potential edge cases that incident responders should be mindful of. With the integration of this new analysis method into Chainsaw, we are confident that cybersecurity professionals will have a powerful tool at their disposal for investigating complex security incidents.

Special thanks go to Alex Kornitzer, WithSecure Lead Software Engineer, for his continued guidance and support in getting this research incorporated into Chainsaw.

Basics of Shimcache and Amcache

Amcache and Shimcache are forensic artifacts found on Windows systems that can be used to analyse execution activity. The Amcache records data about installed applications, while Shimcache logs data about executables introduced to a system. These artifacts are invaluable in analysing execution activity and identifying potential security breaches. However, it should be noted that the information provided by the Amcache and Shimcache is limited, and it is crucial to use additional tools and techniques to conduct a comprehensive analysis of a security incident. For those who are already familiar with these artifacts, we still recommend reading these sections as we cover some key information that is generally not covered in most places.

Shimcache Introduction

Shimcache is a component of the Windows Application Experience and Compatibility feature. It is used for quick lookups on program execution to determine if a compatibility layer (a “shim”) is needed to run the application. It is stored in the `SYSTEM` windows registry hive which can be found from `C:\windows\system32\config\SYSTEM`. This artefact is widely used in the industry to identify malicious binaries that a threat actor may have interacted with.

The list of Shimcache entries is a top-down list of events related to executables. These events are recorded when executables are first ‘shimmed’. This effectively means, an executable was scanned by the Windows operating system to determine the ideal profile to run the executable in. Although the direct circumstances when the Shimcache shims an executable are undocumented, we know that shimming takes place when a user interacts with an executable. This may be simply the user installing a program that is executing it for the first time, or simply creating it on the system. However, one crucial fact to remember is that the Shimcache does not contain entry insertion timestamps, but rather `last modified` timestamps of the referred files.

Amcache Introduction

The Amcache is also a component of the Windows Application Experience and Compatibility feature like the Shimcache. It is a windows registry hive file that contains various metadata on programs, application files, and drivers. It is located at `C:\Windows\appcompat\Programs\Amcache.hve`.

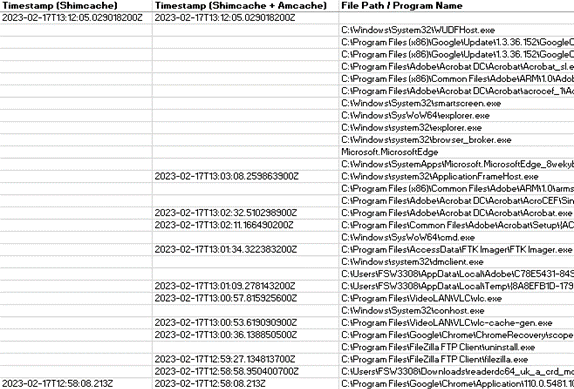

The Amcache contains useful initial execution timestamps that can be used to enrich the timing information of Shimcache entries. Below diagram shows the differences on how many more timestamps can be derived if Amcache enrichment is enabled.

Analysis techniques 2 and 3 utilise the Amcache for further identification of timestamps. We found in our tests that Amcache enrichment leads to 2.7x more timestamps on average as well as providing SHA1 for some of the entries.

Analysis Techniques of Determining Shimcache Insertion Timestamps

The 'analyse' subcommand utilizes series of techniques to identify Shimcache insertion timestamps. The idea of the analysis is to determine accurate insertion timestamps for as many Shimcache entries as possible. This is done to provide defenders more context around what the threat actors may have executed or performed on a host. As threat actors commonly download their tools on disk shortly before execution, the timestamps determined are almost certainly the time of execution, if not shortly before execution.

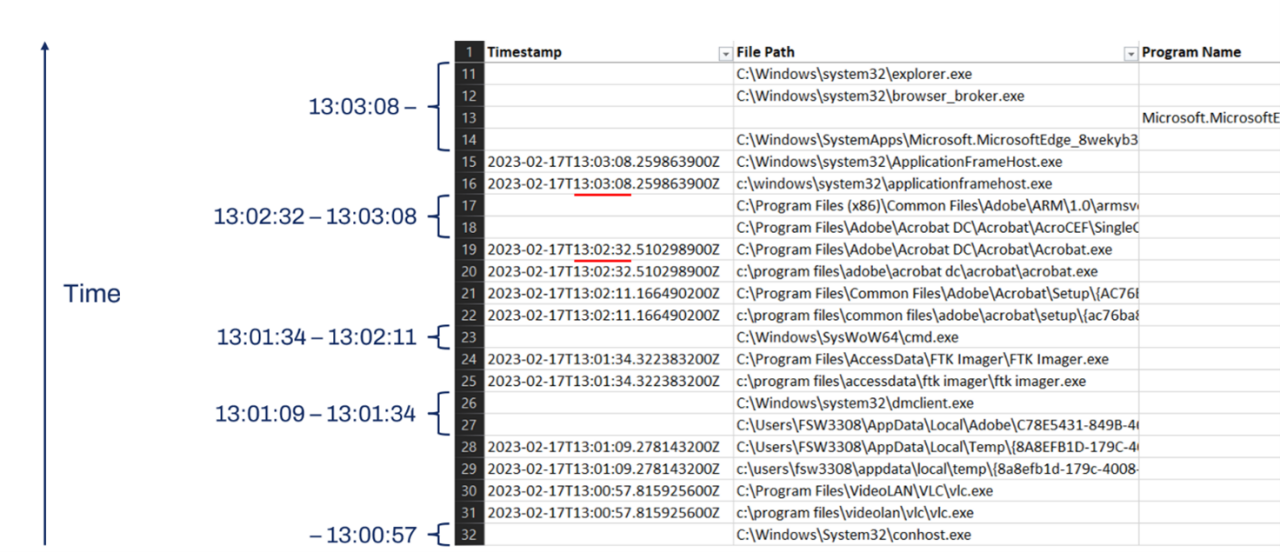

Furthermore, having an accurate timestamp for Shimcache entries means that timing information of surrounding entries can be inferred:

- Every entry that is below a timestamped entry was inserted before the timestamped entry

- Every entry above a timestamped entry was inserted after the timestamped entry

The more timestamps there are, the tighter the time ranges of other entries in the Shimcache become. This allows for more accurate timing information about the existence of a file/program on a system, and in some cases, execution timing. The figure below shows a snippet of the analysis output and demonstrates derived timestamps. It also demonstrates how time ranges for the entries without timestamps can be determined.

As previously mentioned, Shimcache entries are arranged in a top-down list consisting of 1024 entries. The rate at which this list rolls over increases with the device's activity level. Through our engagements, we have discovered that for certain servers, this rollover period can extend up to four months. Thus, this analysis generally way more effective on Windows servers where user interaction is minimal compared to Windows workstations.

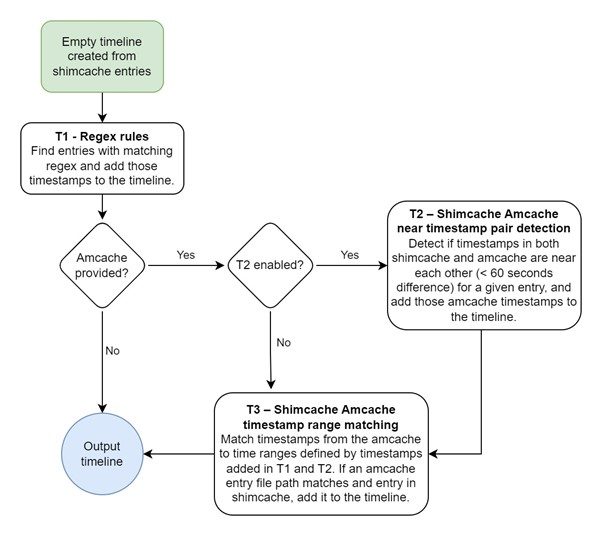

There are three different analysis techniques that can be applied to the Shimcache and Amcache. Techniques 1 and 3 have been applied in an actual incident and are tested, but they have a few caveats. Technique 2 is based on new research. It is not enabled by default since it has a few theoretical edge cases where it produces false results. These three techniques are referenced as:

- Technique 1 (T1) – Regex Rules

- Technique 2 (T2) – Shimcache Amcache Near Timestamp Pair Detection

- Technique 3 (T3) – Shimcache Amcache Timestamp Range Matching

The below figure illustrates the flow of the analysis process.

Technique 1 (T1) – Regex Rules

Chainsaw CLI parameters: '--regexfile <path>' or `-e <pattern>`

During several incident response engagements, WithSecure IR team observed that certain executables have a file last modified timestamp that corresponds to their first execution time. A great example of this also noted in a blog post by Madiant. Such executables are usually automatically downloaded update files or executables related to an installation that are downloaded and executed right after download.

When executed using the above parameters, the analyse plugin of Chainsaw performs the following steps:

- All the Shimcache file paths are converted to lower-case.

- Match the regex rules against the lower-case paths of the entries.

- If the regex matches, the last modified file time of the Shimcache entry is interpreted as the insertion timestamp of the same entry.

Based on our research and incidents, we have provided a list of regex rule matching to such executables. This is available at the Chainsaw GitHub repository. (analysis/shimcache_patterns.txt)

Technique 2 (T2) - Shimcache Amcache Near Timestamp Pair Detection

Chainsaw CLI parameters: `--Amcache <Amcache.hve> --tspair`

If the Shimcache file last modified timestamp and the Amcache key update timestamp for a file are near each other (less than 60 seconds), it is highly likely that the entry was inserted to the Shimcache at one of those timestamps. The Amcache key update timestamp gets interpreted as the Shimcache insertion timestamp in this case.

This technique is not enabled by default since it has a few edge cases where it makes it more prone to produce incorrect timestamps. These cases are covered in the caveats and edge cases section.

Technique 3 (T3) – Shimcache Amcache Timestamp Range Matching

Chainsaw CLI parameters: `--Amcache <Amcache.hve>`

Once technique 1 and optionally 2 are applied, the insertion time ranges of Shimcache entries are determined. So, if an Amcache entry falls within this range and has a matching Shimcache entry with the same file path, it can be deduced that the Shimcache insertion timestamp must be near if not the same as the Amcache timestamp.

Accuracy Caveats and Edge Cases

Because the Shimcache insertion timestamps are interpreted from other timestamps, they are inferred times and will never be completely accurate. This may cause the timeline timestamps to be out of order. An analyst should be aware of these limitations when performing investigations using these techniques and where possible should support their conclusions from other evidence sources.

T1 Caveats

The technique T1 uses the “file last modified” timestamp as the insertion timestamp. The timestamps that come from using this method are always going to be slightly before the actual Shimcache insertion time. This is due to the order of events that lead to the matched executables being inserted to the Shimcache:

- The executable file gets created

- file last modified timestamp set.

- This is the timestamp used by T1 technique.

- Delay. Threat actor typing command to execute, Windows processing etc.

- The executable gets either executed or scanned and inserted to the Shimcache

- This is the actual insertion timestamp that is not availabe at the time of analysis

Depending on the executable, the delay could be milliseconds, seconds, or even minutes at worst. However, even the executables that have longer delays are still worth including. as they can still provide useful timing information in long running timelines with large time gaps between events. Certain executables have more accurate timestamps than others. This factor should be taken into account when picking the regex patterns that are used in the analysis.

T2 Caveats

Maximum Time Difference Between the Timestamp Pair

The current maximum time difference between the timestamps is 60 seconds. This essentially means that there is a +-60 second margin of error on the timestamps. This may introduce discrepancies in the final timeline of events.The Amcache timestamp is interpreted as the Shimcache insertion timestamp.

In some cases, it might be that the Shimcache file last modified timestamp is closer to the actual insertion timestamp. Currently the Amcache key update timestamp is always interpreted as the Shimcache insertion timestamp since it often corresponds to the actual execution time. In some cases, this might introduce inaccuracies to the timestamps.

Shimcache Entry Gets Updated in Place

During testing we identified Windows operating system may update the Shimcache entry in-place instead of creating a new entry at the top. We identified this was possible to replicate following the below specific steps. This can create timestamp detection when a file is updated in-place:

- A file gets scanned but not executed (gets inserted to Shimcache)

- That file is later updated, replaced with a newer version (file last modified time updated)

- The file gets executed right after (timestamp gets updated in-place in Shimcache & gets inserted to Amcache at the same time)

- The timestamps in the Shimcache and Amcache are now near each other, and a false detection gets produced since the Shimcache entry was inserted before the timestamps

T3 Caveats

Wide Time Ranges May Cause Inaccuracies

The wider the time ranges are, the higher the possibility of getting an inaccurate Shimcache Amcache match in a time range.

An extreme example would be where there is only one time range that spans the entirety of the Shimcache. In this example there are only two entries in the timeline with a determined timestamp: one at the bottom and one at the top. Now every Shimcache entry between these two entries is in this same time range. If there is an Amcache entry with a matching file path, it is very likely that the Amcache timestamp matches this time range, since the timespan covers a very long time. This means that even if the Shimcache insertion happened during a completely different time than the Amcache insertion, the Amcache timestamp still gets interpreted as the Shimcache insertion time. If there are multiple Shimcache entries all these entries will be matched to Amcache timestamp as the Shimcache insertion time. This may lead to false timestamps and produce an out-of-order timeline with invalid time ranges.

Out of Order Timestamps

There is a possibility that some of the timestamps inferred with this technique might produce out of order timestamps on the timeline. This is due to the fact that the Amcache key update timestamp might have occurred at a slightly different time than the Shimcache insertion. This is mostly a problem with Shimcache entries that were inserted in a burst during a short time frame.

What's Next?

We understand that the execution artifacts are crucial in incident response investigations, but unfortunately, they often remain undocumented. We hope that the tool, approach, and techniques we presented in this article will provide further insight and value to incident responders.

We utilized experimental, case study, and observational research methods in this research. Our team is working on a separate research project which focuses on reverse engineering critical execution artefacts line by line to gain a deeper understanding of the structure and functionality of these artifacts. We hope to uncover new insights that can be used to make better use of evidence left by threat actors.

At the WithSecure Incident Response Team, we are committed to research and pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. But we are also a friendly bunch! 😊 We encourage you to make use of our tools and reach out to us (cir@withsecure.com) if you have any questions or suggestions for improvements.