Catching Lazarus: Threat Intelligence to Real Detection Logic - Part Two

By Guillaume Couchard, Qimin Wang and Thiam Loong Siew on 23 October, 2020

Introduction

In this second blog post, we will continue to share actionable detection insights for blue teams to defend their organization against the Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group – Lazarus Group. As discussed in the first part of this blog series [1], these detection insights are derived from intelligence contained in a recent report[2] released by the F-Secure Threat Intelligence (TI) Team. From the TI report, we know that the Lazarus Group employed varying techniques across the MITRE ATT&CK® Matrix[3] in their attack. We covered three phases in the first blog post: Initial Access, Execution, and Persistence, and we discussed part of the Defense Evasion phase.

The remaining techniques in the defense evasion phase will be covered in this blog post, as well as the Credential Access, Lateral Movement and Command & Control phases. The actions performed within these later phases allow threat actors to establish a greater foothold on the target organization’s network, and are therefore critically important for defenders to detect.

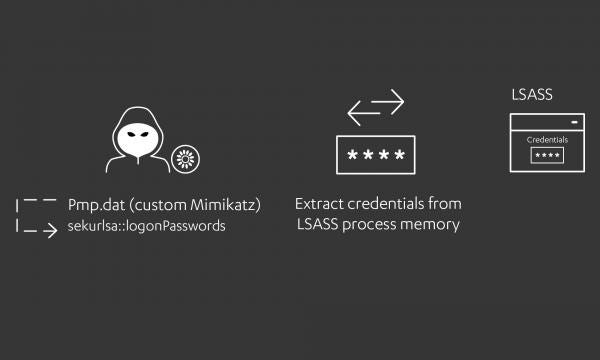

The Sigma rules created for the techniques discussed in this blog post, are marked in bold in the table below and are provided in the F-Secure Countercept GitHub repository[4]. Existing Sigma rules are also listed below, as some techniques were already covered.

Defense Evasion

T1055.002 – Process Injection: Portable Executable (PE) Injection

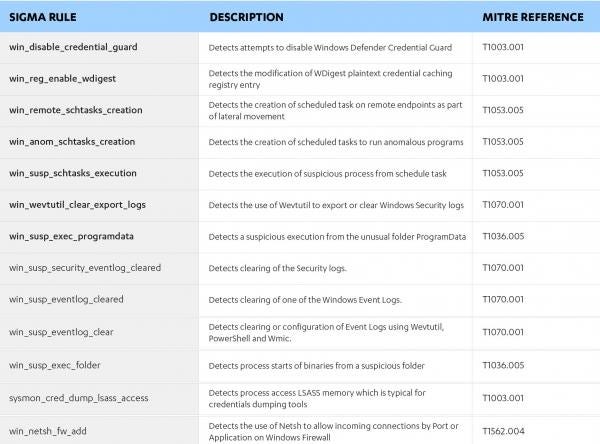

Some of the malware from the Lazarus Group’s campaign had the capability to perform Portable Executable (PE) injection to load additional payloads. For example, the “NTUSER.cat” binary had the capability to load encrypted PE files from disk into its own process memory, decrypt the PE file, and then inject them into another process, namely Explorer.exe.

This is a common technique to evade traditional defenses (such as anti-virus software) and focuses on the inspection of artefacts written to disk, as the malicious content is only decrypted in memory and does not exist on disk in plaintext. Furthermore, injecting malicious content into a separate legitimate process allows subsequent malicious activities to masquerade as the normal behavior of the legitimate process. F-Secure has published a separate blogpost[5] that explains the different types of process injection in detail.

Detection

It is difficult to detect process injection with rules that look for process anomalies. For example, it could be perfectly normal for Explorer.exe to launch Cmd.exe to perform administrative tasks. In the case where malicious code is injected into Explorer.exe to launch a Cmd shell for further commands, process creation logs would also show Explorer.exe launching Cmd.exe.

At F-Secure Countercept, we make use of advanced memory scanning techniques to detect instances of process injection. This involves inspecting process memory in real-time and looking for anomalies which are indicators of process injection. For example, a basic scanning technique could look for process memory regions which are executable but are not of the type MEM_IMAGE. This would indicate that the process memory region is not “backed by disk” and could be an artifact of process injection. This example is just the tip of the iceberg and there are many other complex memory anomalies that can be examined to identify suspicious memory regions.

Although in-memory detection is often tackled through anti-virus or EDR software, blue teams can still leverage open source capabilities to alert on potential process injection. For example, SpecterOps has published an excellent write-up on the procedures of crafting the detection logic for a specific type of process injection known as process hollowing [6]. In the three-part blogpost, it was determined that neither process creation nor process access logs can be used on their own to identify process hollowing due to the significant number of false positives. Instead, a hunt query using Jupyter Notebooks was more appropriate in dealing with the complexities of process injection detection, where different types of process logs were correlated to filter for a sequence of events consistent with process hollowing. There are also several open-source tools – such as ‘hollows_hunter’[7] - which can provide blue teams with the ability to scan endpoints for suspicious memory regions.

In addition to detecting process injection, another powerful threat hunting technique is to look for the execution of rare executables and binaries with uncommon extensions. In the case of the Lazarus Group, the binary with the “.CAT” extension was used to read the configuration file with the “.SDB” extension, and then to inject the referenced files into another process. A hunt query looking for rare executables would often catch this kind of behavior.

T1070.001 – Indicator Removal on Host: Clear Windows Event Logs

To decrease the chances of being detected, the Lazarus Group removed evidence of their activity as they moved within the victim network. For instance, they were observed using the Wevtutil tool to export Windows security event logs:

cmd.exe /c "wevtutil epl security "/q:*[System[(EventID=4778 or EventID=4624)]]" c:\users\public\evt2.dat >C:\Windows\TEMP\TMP1AC9.tmp 2>&1"In the command snippet shown above, we can see that the Lazarus Group exported copies of two Event IDs with the Wevtutil tool. These Event IDs, 4778 and 4624, respectively log events showing when a user reconnects to a disconnected terminal (meaning that user previously had logged in to that terminal), and when a user successfully logs into a machine.

Subsequently, all 4778 and 4624 events pertaining to the compromised user accounts were removed and could not be found during the investigation of the Windows Event Logs. This made it challenging to piece together the movement of the attacker during the incident response investigation.

Detection

Although the specific technique used to clear the event logs was not identified in the TI report, blue teams can still build detection logic for known techniques. As the Lazarus group used the Wevtutil tool to export Event Logs we can first focus on how this tool can be utilized to clear event logs:

wevtutil cl <Logname>

There are two existing Sigma rules[8][9] to detect Windows Event Logs being cleared. Both rules provide suitable detection coverage, but our testing showed that they generate a high number of false positives related to legitimate administrative activities. The number of false positives can be reduced if we focus specifically on the Security logs, also referred to as Audit logs. Another Sigma rule[10] uses this approach, and looks for Event IDs 517 and 1102 (both mean that the Audit log was cleared but on different Windows versions). This rule is powerful as it detects Security logs being cleared regardless of the command used by the attacker.

However, none of the existing rules look for the Wevtutil tool being used to export Security logs, as used by the Lazarus Group. We created a Sigma rule to detect both exporting and clearing of Security logs using the Wevtutil tool, so that defenders can get insight into this activity happening on their estate. The command for clearing logs, “cl” (or “clear-log”), when it is focused on the Security logs, yields significantly fewer false positives based on historical endpoint data from F-Secure Countercept. The Sigma rule created to detect this behavior can be found on our GitHub and is named win_wevtutil_clear_export_logs. The executable “MsSense.exe” is excluded as it is used for legitimate purposes to export the Security logs by Windows Defender Advanced Threat Protection.

Our advice would be to implement all the above rules with different values for the “level” field based on the false-positive rate. As the “level” corresponds to the severity for the rule, we would recommend that rules that have a low false positive rate have a “critical” or “high” level, whereas rules that are more prone to false-positives should be “low” or “medium”.

However, as pointed out at the beginning of this section, there are many other techniques that a threat actor can use to clear Event Logs without using the Wevtutil tool. Furthermore, while we are only focusing on the clearing of Event Logs, an attacker could also disable log generation or hide from Event Tracing for Windows (ETW)[10]. ETW is the kernel-level event tracing mechanism built into the Windows operating system that handles the logging of all system events. In fact, there are so many techniques that could be used to disable or hide from ETW that it could fit in a separate blog post series. As we are focusing on generating detection from the Lazarus TI report, they fall outside the scope of this blog post.

Regardless of whether the attacker clears the logs or disables ETW, this section underlines the importance of streaming logs to a central source in real-time. With this implemented, if an attacker clears the logs on an endpoint – as the Lazarus Group did - it would only affect the logs stored locally and therefore blue teams would not lose valuable forensic information. Furthermore, streaming logs to a central source provides the detection opportunity to alert when an endpoint stops sending logs while it is still online, this provides another “tripwire” for detecting suspicious endpoint activity.

T1562.001 – Impair Defenses: Disable or Modify Tools

Disabling Credential Guard

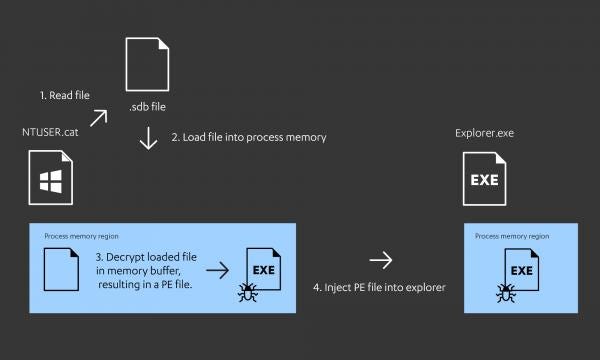

The Lazarus group were observed using a custom version of Mimikatz to harvest credentials from LSASS memory. To accomplish this, they first disabled Windows Defender Credential Guard.

Older versions of Windows used to store credentials in the memory of the Local Security Authority (LSA) process. From Windows 10 onwards, credentials used by the operating system are stored in a new component called the isolated LSA, also known as the “Credential Guard”.[11] This isolated LSA process (LSAIso.exe) is protected using virtualization-based security and is not accessible to the rest of the operating system except by the LSASS process through Remote Procedure Calls (RPC). Therefore, threat actors often disable this security mechanism before attempting to extract system credentials.

By modifying the registry entry shown below, the Lazarus Group disabled Credential Guard which caused LSA to store credentials in its process memory instead:

cmd.exe /c reg add HKLM\\System\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\Lsa /v LsaCfgFlags /t REG_DWORD /d 0 /f 2>&1

Detection

As the command above modifies the registry entry 'HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Control\LSA\LsaCfgFlags', the detection will be based on the registry_event and process_creation log sources to be able to monitor any registry modification.

Using the registry_event log source, we must filter for any event of "SetValue" or "AddValue" with the value of 'DWORD (0x00000000)' in the above-mentioned registry entry. This log source is important for detection as we can monitor any changes to this registry entry, regardless of the tool used by the attacker.

That said, if there is an issue with the registry event log (let’s say an attacker clears or tampers with logs, as previously mentioned), it is still good to have something for the process creation logs. Here we could look for the Reg.exe command with the arguments ‘add HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Control\LSA /v LsaCfgFlags /t REG_DWORD /d 0’.

This works well, but our telemetry showed that we can expand that detection rule by restricting the command line arguments only to “LsaCfgFlags” and still have a very low false positive rate. This way it will also show an attacker deleting that registry entry (which also disables CredentialGuard) or querying it (to check if CredentialGuard is enabled).

Based on our telemetry, querying or modifying the Credential Guard registry value has a very low false positive rate. The Sigma rule created to detect this behavior can be found on our GitHub and is named win_disable_credential_guard.

Credential Access

T1003.001 – OS Credential Dumping: LSASS Memory

Once Credential Guard has been disabled, it is significantly easier to extract credential material from LSASS’ memory. The Lazarus group took advantage of that by performing the following procedures:

Enabling storage of credentials in plaintext (WDigest)

WDigest credential caching is a legacy authentication protocol.[12] This protocol causes LSASS to store credentials in its memory in plain text and is enabled by default on Windows Server versions prior to Server 2012 R2.[13] While it is disabled by default on more recent versions of Windows, threat actors can modify the registry to enable WDigest credential caching. The Lazarus Group were observed using the following command to achieve this:

cmd.exe /c reg add HKLM\\System\\CurrentControlSet\\Control\\SecurityProviders\\WDigest /v UseLogonCredential /t REG_DWORD /d 1 /f 2>&1Detecting modification of WDigest plaintext credential caching registry entry

The detection for this technique is similar to the detection of Credential Guard being disabled as discussed earlier in this blog post. Any registry event or process creation log where the registry entry 'HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Control\SecurityProviders\WDigest\UseLogonCredential' has its "DWORD" value modified to 1 is an indicator of this technique being used. While there is an existing Sigma rule[14] which includes the detection for this behavior, it also includes detections for other techniques specific to another APT group. As such, we have written a separate rule specifically detecting the modification of the WDigest credential caching registry key. During our testing of this detection rule, we had almost no false positives except for a few instances caused by vulnerability management scripts. If this detection rule causes too many false positives in your environment, you could modify the rule to only focus on the modification of the registry entry to the value ”1”. The Sigma rule created to detect this behavior can be found on our GitHub and is named win_reg_enable_wdigest.

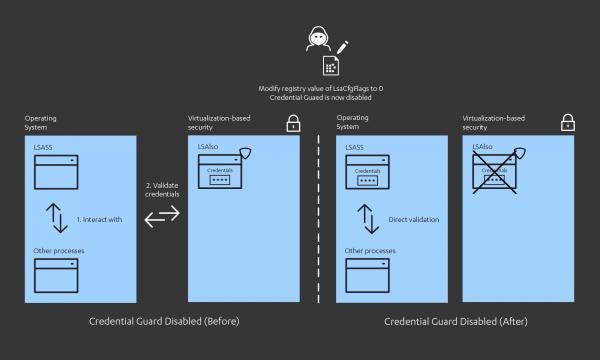

Using standard Mimikatz functions to dump credentials

With the previous preparation steps completed; threat actors can then use tools like Mimikatz to harvest credentials from the LSASS process memory.

While the Lazarus Group were observed using a custom or simply a renamed version of Mimikatz, traces of the commonly used functions of Mimikatz could still be identified through the command line arguments, such as “privilege” and “sekurlsa”:

cmd.exe c:\users\public\pmp.dat privilege::debug sekurlsa::logonPasswordsDetecting Usage of Mimikatz-like tools

Since the Lazarus Group did not obfuscate commonly used functions from the Mimikatz tool, blue teams can detect commonly used Mimikatz functions in command line arguments with an existing Sigma rule[15].

Apart from the quick win above, blue teams can also hunt for processes accessing the LSASS process. For example, running Mimikatz with the arguments SEKURLSA::LogonPasswords will cause Mimikatz to dump password data from the LSASS process memory for recently logged on accounts as well as services running under the context of user credentials[16]. This generates a process access event, which is created when a process accesses another process. This behavior usually occurs as a result of reading and writing to the memory address space of the target process[17]. In this case, the target process is Lsass.exe and credentials are read from its address space. An existing Sigma rule is available to detect this behavior[18].

Lateral Movement

T1053.005 – Scheduled Task/Job: Scheduled Task

Leveraging scheduled tasks for lateral movement is a very common technique. The Lazarus Group used scheduled tasks to modify the “HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Lsa\Security Packages” registry key on a remote machine:

cmd.exe /c "schtasks /Create /S <IP ADDRESS> /P <PASSWORD>! /U "<DOMAIN>\<USER> " /TN "MSC" /TR "reg add /"HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Lsa/" /v /"Security Packages/" /t REG_MULTI_SZ /d /"ldap/" /f" /SC ONSTART /RU SYSTEM /F >C:\Windows\TEMP\TMPD2E6.tmp 2>&1"Detection

Simply detecting the use of the Schtasks utility can be challenging as it is widely used by legitimate Windows applications and for administrative purposes. However, we can reduce the number of false positives by detecting the creation of a scheduled task for the purpose of launching anomalous programs.

Suspicious scheduled task creation:

The Lazarus Group's scheduled task creation can be considered anomalous behavior as Reg.exe is rarely executed by the scheduled task utility. Therefore, monitoring for the use of the Reg.exe utility in a scheduled task creation command can prove to be an effective detection strategy. Another example for anomalous programs originating from a scheduled task is encoded PowerShell. While encoded PowerShell alone is not a high-fidelity detection, we have found that hunting for scheduled tasks being created with encoded PowerShell as the “scheduled action” has a low false positive rate, often indicating persistence or lateral movement activity. The Sigma rule created to detect this behavior can be found on our GitHub and is named win_anom_schtasks_creation.

Remote scheduled task creation:

Another opportunity for detection would be the use of command line options "/S", “/U” and "/P", which are used to specify the IP address for a remote computer, the user context under which Schtasks.exe should run, and the password for a given user context respectively. While these command line options can be used legitimately to create scheduled tasks on remote machines, they are not commonly observed based on historical data from F-Secure Countercept. The Sigma rule created to detect this behavior can be found on our GitHub and is named win_remote_schtasks_creation.

Suspicious scheduled task execution:

While the creation of remote scheduled tasks is often observed on the first compromised host to move laterally to other hosts in the network, the tasks themselves will eventually execute on these hosts. Thus, it would also be valuable to build detections for suspicious processes that are executed by the Windows Task Scheduler.

This can be achieved by detecting a combination of suspicious processes or processes that are commonly used to launch suspicious scripts; examples include Cmd.exe, Powershell.exe, Cscript.exe and Reg.exe. For these processes we can filter for where the parent process is either Windows Task Scheduler Service (“svchost.exe -k netsvcs –p -s Schedule”) or Windows Task Scheduler Engine (Taskeng.exe). We observed some difference in scheduled tasks execution in different versions of Windows. In newer versions such as Windows 10 and Windows Server 2016, scheduled tasks are executed directly from Windows Task Scheduler Service where older versions like Windows 7 and Windows Server 2012 are executed from Windows Task Scheduler Engine.

The Sigma rule created to detect this behavior can be found on our GitHub and is named win_susp_schtasks_execution. However, it is worth noting that during testing we found that without any tuning this rule will often trigger false positives, especially in environments where scheduled tasks are used to regularly run custom administrative scripts. Therefore, blue teams should identify and exclude any known administrative scripts in the detection rule before implementation in production environments.

T1021.001 – Remote services: Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP)

T1021.005 – Remote Services: Virtual Network Computing (VNC)

With the credentials acquired using the techniques explained in the Credential Access section, the Lazarus Group were able to move laterally across the network. To achieve this, they made use of common remote services such as RDP and VNC.

Detection

It is challenging to write detection rules for the use of RDP and VNC as they are generally widely used within networks of all sizes for legitimate purposes. Context is crucial for such activities, and malicious activity is often only apparent by looking at a combination of user and endpoint activity across many systems on the network over hours or days, rather than focusing on a single event on a single endpoint.

To combat this detection challenge, at F-Secure Countercept we use User Behavior Analytics (UBA), a technique focused on detecting when users perform new activity that they have not performed historically.

Traditionally, blue teams’ focus has been on detecting generic "bad" behavior. As with most of the content in this detection report, it involves searching for a wide variety of offensive tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) and general anomalies that relate to them. UBA differs from this in that it focuses on detecting anomalies based on user behavior, regardless of whether any offensive techniques have been used. This focus makes it a perfect complement to our traditional focus and has the potential to fill in some key detection gaps.

For example, by analyzing 4624 and 4648 logon events from Windows security Event Logs, it is possible to identify when a standard user account authenticates to multiple new (for that user) endpoints, which can be an indication of lateral movement.

Command and Control

TA0011 – Command and Control

The Lazarus Group leveraged a network backdoor implant to communicate with the victim’s network. The built-in Windows utility Netsh was used to open a port in the Windows Firewall when the port number was passed as an input argument to the implant Mcc.exe, as seen below:

C:\ProgramData\mcc.exe 3388 netsh firewall add portopening TCP 3388 AssistanceThe network backdoor then listens on the opened port and can execute any command it receives via the listening port.[19] In order do that, the backdoor executable will run Cmd.exe with the command that it received from the C&C server.

Detection

Detection for this type of network backdoor on the endpoint can be achieved by looking for the process creation of the Netsh utility with command line arguments “firewall add portopening”. An existing Sigma rule is already available to detect when a port or application is allowed through the firewall via the Netsh utility[20].

However, this detection is also prone to false positives from legitimate administrative processes such as Spoolsv.exe (the spooler service which manages print jobs). Therefore, blue teams should verify the parent process and correlate with other events to exclude false positives.

In this scenario, a hunt query can be an effective complement to the existing detection rule. Defenders can query for Netsh.exe processes launched with arguments containing “firewall add portopening” and then aggregate the results based on the parent process. This should return a list of processes that use Netsh to open a port in the Windows Firewall. Blue teams can then filter out known legitimate processes from the hunt results and whitelist them in the detection rule.

Another suspicious execution characteristic of the mcc.exe binary was its location on disk. The “C:\ProgramData\” directory is a commonly used location for attackers / malware as it is writeable by any authenticated user and has execution permissions by default on Windows. Although legitimate programs are often installed and executed from within the “C:\ProgramData” directory, these executables are often stored within subfolders specific to that application. In contrast to this normal behavior, the mcc.exe binary used by the Lazarus Group was not stored in a subdirectory of the “C:\ProgramData” folder and was instead stored directly under the “ProgramData” directory. Combining this information with the knowledge that the mcc.exe binary would launch cmd.exe as a child process to execute received commands, we can build a detection for executables being launched where the parent executable is located in the “root” of the “C:\ProgramData” folder.

This rule can be found on our GitHub and is named win_susp_exec_programdata. During testing this rule resulted in a very low false positive rate when run against F-Secure Countercept endpoint data.

Conclusion

The Lazarus Group invested significant effort into evading defenses in this instance. This is apparent from the breakdown of the campaign and the association of the various TTPs to the MITRE ATT&CK framework. The Group demonstrated a strong sense of operational security awareness by disabling built-in defenses, removing indicators of compromise, and leveraging process injection and signed binaries to hide their presence and blend in with normal network traffic.

Our findings highlight the importance of capturing and leveraging endpoint telemetry for early detection of compromise as well as increased visibility into the threat actor’s chain of activities following initial access.

Most of the endpoint telemetry used for detection throughout this post series can be easily logged by using existing Windows utilities. For example, System Monitor (Sysmon)[21] can be installed on endpoints to log specific events such as process creation, image load and process access. Alternatively, blue teams can directly tap into Event Tracing for Windows (ETW)[22], which is a powerful kernel-level trace collection system built-in to the Windows Operating System. ETW can also be used by Sysmon to further enhance visibility into endpoint behavior.

Although we have provided Sigma rules throughout this blog series, this does not necessarily mean that they can be used “as is” to produce detection results. In fact, a lot of work needs to be done before rule implementation. This involves building a data pipeline, aggregating the correct datasets, and adapting the Sigma rules to the existing log collection/SIEM formats before the detection rules can be used to alert on suspicious activity.

We believe that these two blog posts can be of great use to organizations seeking to improve their detection capabilities. Although the provided Sigma rules were created from Threat Intelligence on the Lazarus Group, the detection logic covers a wide range of TTPs that are used by a wide range of threat actors. The provided Sigma rules have not been directly implemented in a real production environment, but our internal rules follow a similar format, are built with similar detection logic, and have been tested with existing telemetry. This means that common false positives have been studied and excluded, which is a benefit for smaller organizations which might not have the resources to do this kind of work, but also for larger organizations to improve their detection at scale.

All of the Sigma rules referenced throughout this blog series can be found here.